Can Section 144 Wipe Out Parliament?

Another point of uncertainty in Thailand

In recent days, national attention has continued to be focused on the tensions with Cambodia. The next General Border Committee (GBC) meeting, now to be held in Malaysia instead of Cambodia due to a request made by the Thai side, will be happening this week. We should have a better understanding of where things stand on the border after this meeting. Meanwhile, the government remains under pressure, with another large rally held on Saturday against the government at Victory Monument. Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra secured a final extension in submitting her defense for her Hun Sen phone call case from the Constitutional Court. Thaksin Shinawatra’s hospital stay case is set to receive a ruling on September 9th. More on that in the days ahead.

Today I want to focus on another legal case that has so far received essentially no attention in the international press but sets an important precedent that could prove momentous for Thai politics later on. On August 1st, the Constitutional Court terminated Deputy House Speaker Pichet Chuamuangphan of his status as MP and banned him from running for office for ten years over violating Section 144 of the 2017 Constitution. What exactly is Section 144, and why is it so important?

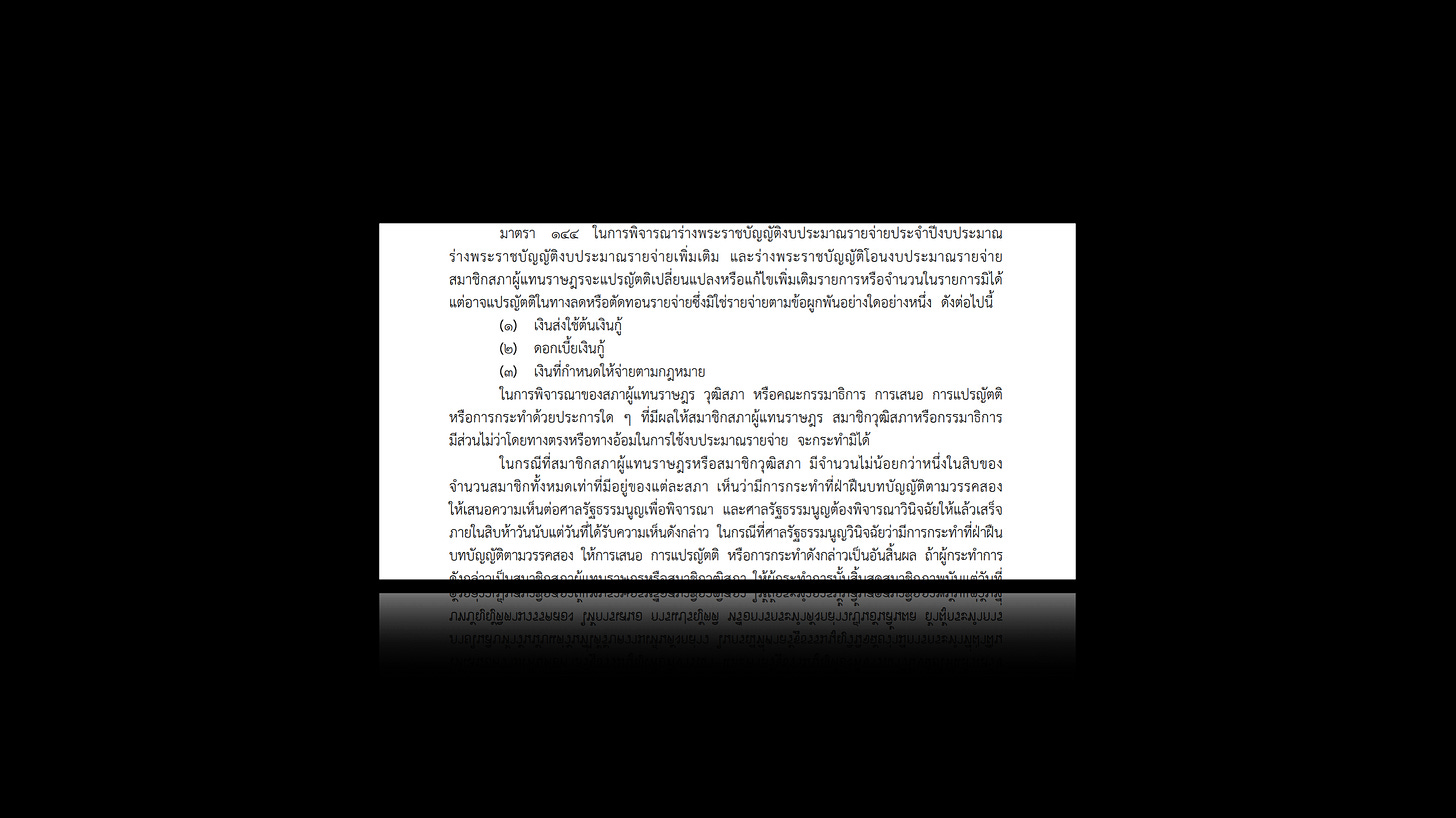

This section states:

In the consideration of an annual appropriations bill, supplementary appropriations bill, and transfer of appropriations bill, a Member of the House of Representatives shall not submit a motion altering or adding any item or amount in an item to the bill, but may submit a motion reducing or abridging the expenditures which are not expenditures according to any of the following obligations:

(1) money for payment of the principal of a loan;

(2) interest on a loan;

(3) money payable in accordance with the law.

In consideration by the House of Representatives, the Senate or a committee, any proposal, submission of a motion or commission of any act, which results in direct or indirect involvement by Members of the House of Representatives, Senators or members of a committee in the use of the appropriations, shall not be permitted.

Let’s break this down. The first portion of the clause essentially states that an MP cannot amend the budget by adding expenditures. This is because revenue generation is under the purview of the executive branch, and so the legislative branch cannot spend more than what the government has proposed. Quite straightforward.

The second portion of the section, however, is more interesting. As iLaw explains: “Section 144’s second clause prohibits MPs, Senators, and committee members from amending or taking any action that would allow MPs, Senators, or committee members to take a part in utilizing these funds, either directly or indirectly. The reason for this clause is to ensure that there is no amendment of the budget so it would be allocated to their own areas, as there has been in the past, such as in using the budget to build pavilions, football fields, bridges, etc.”

This second clause is what led to Pichet’s downfall; as Thai PBS summarizes, “The case against Pichet was initiated by People’s Party MP Pannasilp Nuamjerm, seconded by 120 MPs, accusing him of abusing his authority when he diverted 147 million baht, intended for three projects for the Office of the Secretariat of the House of Representatives, to his electoral constituency in Chiang Rai province.” Pichet is thus the first politician in Thailand to ever be punished for violating Section 144.

What are the implications of this ruling? The most immediate is that it will further heighten legislators’ care in how they approach budgetary issues. I know that some MPs favor amending Section 144 because it prevents them from what they see as “properly” taking care of their constituencies, as they can no longer divert funds to their own areas. Amendment seems highly unlikely at this point because constitutional reform as a whole is a project that for now appears to be going nowhere. And so with no change to the status quo on the horizon, MPs will have to see Pichet’s case as a cautionary tale.

But the first-ever practical enforcement of this portion of the constitution sets a precedent for a potentially more explosive legal case.1

Earlier this year, a group of petitioners had asked the National Anti-Corruption Commission to investigate whether or not the cabinet had violated Section 144. Essentially, the case revolves around amendments to the 2025 budget. In July 2024, the House of Representatives approved the 2025 budget in its first reading, but prior to the second reading, the Srettha Thavisin cabinet had reallocated 35 billion baht from a budget to be used for debt payment to state-run banks to the Pheu Thai Party’s flagship 10,000 baht digital wallet scheme instead.

As the Bangkok Post writes, according to the petitioners, “The House committee scrutinizing the budget acquiesced despite the constitution prohibiting such action…Section 144 of the constitution prohibits the slashing of budget allocations used to fulfill legal obligations, particularly allocations set aside for debt payment to banks under Section 28 of the Financial and Fiscal Discipline Act.” In addition, “another 1.25 billion baht was diverted from the central fund to a fund for former parliamentarians, which violated Section 144 (2) of the constitution, which prohibits MPs or senators from diverting budget allocations for personal benefits.”

Overall, therefore, a finding that Section 144 was violated could impact all MPs and Senators who voted for the budget, along with the Paetongtarn Shinawatra cabinet which is still implementing remnants of the 10,000 baht giveaway plan. That would be equivalent to a political wipeout: a total of 309 MPs and 175 senators voted for this bill. The only MPs left would essentially be those in the opposition who did not vote for the budget. Just like in Pichet’s case, the punishment could be severe, as stated by the 2017 Constitution:

If the person who commits such violation is a Member of the House of Representatives or a Senator, his or her membership shall be terminated as from the date the Constitutional Court renders the decision. The right of such person to stand for election shall also be revoked. In the case where the Council of Ministers commits or approves the commission of such action, or is aware of the action but fails to order its cessation, the 51 Council of Ministers shall vacate office en masse as from the date the Constitutional Court renders the decision, and the right to stand for election of the ministers whose offices are vacated shall also be revoked unless he or she can prove that he or she was not present in the meeting at the time of passing the resolution.

It is difficult to predict the consequences of such a ruling because it would be entirely unprecedented. The last time such a mass disqualification of politicians happened would be in the aftermath of the dissolution of the Thai Rak Thai Party in 2007, when 111 politicians who had served in the party were disqualified from office for five years. A ruling against 309 MPs would outstrip that. It would lead to almost the equivalent of a national election — byelections in a massive number of constituencies — but without the MPs who had cultivated these strongholds for years.

At this point, the National Anti-Corruption Commission has accepted the petition but has not made a decision on whether to forward it to the Constitutional Court. It is thus too early for us to say whether there is a genuine danger that a parliamentary wipeout will happen. But the fact that it is at all possible adds even more uncertainty to an already combustible situation in Thai politics.

The phrase "properly taking care of their constituencies" is quite mysterious.