Ceasefire Talks Between Thailand and Cambodia Scheduled

What we know so far

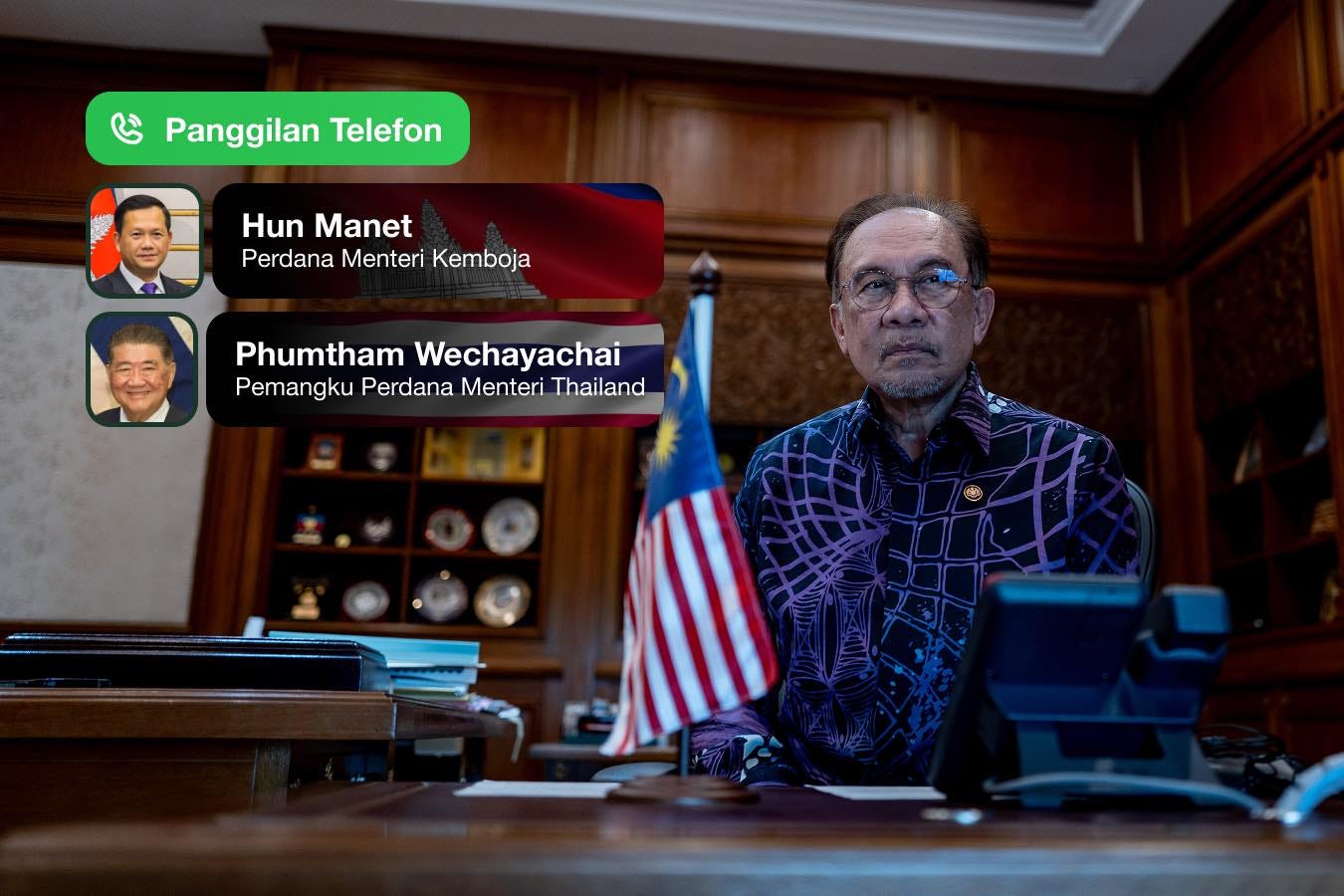

US President Donald Trump made an unexpected intervention yesterday, posting on Truth Social that he was attempting to arrange a ceasefire between Thailand and Cambodia. After calling both Acting Thai Prime Minister Phumtham Wechayachai and Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet, Trump wrote that “Both Parties are looking for an immediate Ceasefire and Peace. They are also looking to get back to the “Trading Table” with the United States, which we think is inappropriate to do until such time as the fighting STOPS.”

Trump’s move likely put a significant amount of pressure on both governments to find a way to wrap up hostilities as soon as possible, as both Thailand and Cambodia are racing to negotiate with the United States on reducing their 36% tariff rates which are set to go into effect on August 1st.1 Now, talks are set to begin. This evening, the Thai government announced that Phumtham, along with a delegation including Foreign Minister Maris Sangiampongsa and Deputy Defense Minister Nattaphon Narkphanit will be meeting Hun Manet tomorrow at 3 PM in Malaysia, at the invitation of Malaysian Prime Minister and ASEAN Chairman Anwar Ibrahim.

Here is what I see as the current state of play:

1. The beginning of talks does not necessarily mean an immediate end to hostilities. The Royal Thai Army has maintained that fighting from Cambodia has not stopped. A deputy spokesman for the RTA said today that “negotiating is the responsibility of the government; the army’s responsibility is to conduct operations while an end to shooting is still unclear.” Even as the government was announcing the scheduling of the talks in Malaysia, local media were still reporting of a rocket strike in Sisaket province.

2. It is still unclear what each side will demand during the negotiations. Yes, both sides will be working towards a ceasefire, but we do not know for certain what either side is going to propose. As Kittitouch Chaiprasith wrote, the core demands from the Thai side is likely to be 1) an insistence on using the “1:50,000” map as opposed to Cambodia’s preferred “1:200,000” map2, along with 2) demanding that Cambodia refrain from attempting to take over Thai territory in four areas by appealing to the International Court of Justice (ICJ).3 In a statement put out by pheu Thai, Government Spokesperson Jirayu Houngsub has insisted that the government “will not discuss acceptance of the 1:200,000 map as proposed by Cambodia…Thailand continues to uphold the 1:50,000 map that it has continually used.” Yet if Cambodia disagrees with these core principles from the Thai side, the negotiations are likely to reach an impasse. I would not be surprised if the conclusion reached at the end of the talks is simply an agreement to keep talking, and a ceasefire in the interim. (I will also say this over and over again: it’s hard to know what constitutes, to the key decision-makers on both sides, a satisfactory conclusion to this crisis when there is still so much uncertainty about what caused it — at its core this is unlikely to be a mere conflict over territory).

3. The Thai negotiating team is operating under heavy domestic suspicion. Here, the lingering effects of now-suspended Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra’s phone call with Cambodia’s de facto leader Hun Sen, where she told “Uncle” she would “take care” of whatever he wanted, continues to haunt the government. I do not have opinion polling to back this up, but overwhelmingly online sentiment on social media is immense skepticism of Phumtham and the Pheu Thai team and whether they will do enough to defend the Thai national interest. It is noteworthy that Jirayu had to say in his statement that “No government or individual would ever sell out their own country.” The fact that this had to be said showed that the government is aware of what many Thais are thinking. Wassana Nanuam, a prominent military reporter, has written that during ceasefire talks there should “members of the military who know the area well” in order to prevent negotiating a bad deal. But there were no members of the military announced as part of the negotiating team, only the deputy defense minister who was a former general.

Indeed, I am not sure what the Thai negotiating team can achieve that will blunt public criticism in the face of such suspicion. The fact that several Thai civilians and troops have died over the course of the past few days has raised public anger at Cambodia to a fever pitch. If Phumtham returns with any sort of agreement that is widely viewed inside Thailand as having been insufficiently protective of the national interest, this already wobbly government is going to become a fresh target of anger.

The latest we heard was that Finance Minister Pichai Chunhavijara was due to submit Thailand’s final proposal to the United States, but that was before the start of the border conflict.

Thailand prefers to use the more detailed 1:50,000 map, which is more detailed than the Cambodian 1:200,000 map (first developed by French surveyors). As The Nation explains, “In certain areas, Thailand’s maps may show the boundary passing through one location, while Cambodia’s maps indicate it lies hundreds of metres—or even several kilometres—away.”

Thailand does not recognize the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ and the 1962 ruling favoring Cambodia based on colonial-era maps that Siam could not contest means that successive Thai governments have favored bilateral negotiation, currently conducted through the Joint Boundary Commission.