Looking Beyond "Why Nations Fail"

Why Thailand's national conversation needs a firmer foundation

If a book called Why Nations Fail becomes of interest in your country, that should be a pretty good sign that things are not going well. Unfortunately, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson’s Nobel Prize-winning research has been the talk of the town in Thai social media over the past few weeks.

Interest in this book, in my recollection, stems from when Pat Pataranutaporn, a Thai researcher on AI at MIT, referenced the book in a Facebook post last year where he criticized an unnamed Thai university’s prioritization of ceremony over substance at an event he attended. Acemoglu and Robinson’s research, Pat wrote, had showed that national success is the result of institutions — and even these pointless academic ceremonies have a ripple effect. At a time when people are becoming increasingly disillusioned with both the state of politics and the economy, it is not surprising that such a post would attract attention. Discussion of Why Nations Fail picked up again when Kiatnakin Phatra Chief Economist Pipat Luengnaruemitchai wrote another Facebook post urging people to read it. “Beware of Thailand turning into a chapter of this book,” he said.

Then, to cap it all off, BBC Thai invited James Robinson himself to give an interview on his perspectives on Thailand. Robinson admits that he has only a “surface-level”1 knowledge of Thailand, but he offers the following insights:

Thailand’s institutions are extractive rather than inclusive (the key argument in Why Nations Fail!). He highlights how the military, unlike in places like South Korea, have yet to withdraw from politics.

Drawing on research from The Narrow Corridor (also co-authored with Acemoglu), Robinson believes that Thailand, like many Latin American countries, is a “Paper Leviathan,” possessing both a weak state and society that is inhibited by clientelism and corruption.

Offering optimism, Robinson says that Thailand is still “in the game” because it has not become a wholly failed state and can still reach the “narrow corridor” of a mobilized society and responsive state. Thailand also has the advantage of already possessing excellent cultural capital.

A “Mythologized Narrative”

So, what should we make of all this?

Of course, I appreciate all that Acemoglu, Robinson, and Simon Johnson (henceforth AJR) have done to bring attention to the important role of political institutions in determining economic outcomes. As Maia Mindel wrote last year,

“Why did AJR win their Nobel? Not because their research is the be all, end all of the literature, but because it opened the gates to a lot of discussion that still continues to shape the literature — the entire field of development is, in some way, responding to their highly imperfect work.”

But the imperfections should also be taken seriously, especially when readers are taking their arguments at face value. From the moment that Pat Pataranutaporn’s original Facebook post went viral, I have been wary about whether or not it would spark the conversations that I believe Thailand really must be having. (Maybe my wariness is natural given that I am a political scientist and the major insight that AJR brings — institutions matter! — is not exactly a mind blowing revelation in our field). So let me put some teeth on this critique.

The most common criticism of AJR’s work is that it fails to explain how China, whose institutions are far from the ideal type of inclusive institutions that AJR advocates, developed. But Yuen Yuen Ang, a professor of political economy at Johns Hopkins University, points out that their theory also fails to adequately explain how even Western countries — the exemplars of inclusive institutions — themselves developed. As she writes:

Even among the ruling class, it was no “level playing field”. During America’s phase of rapid industrialization, known as the Gilded Age (roughly 1880-1900), prosperity was accompanied by inequality and corruption. Robber barons publicly championed free-market principles while privately benefiting from state-supplied privileges and protection. Ordinary citizens bore the burden of bailing out companies that were too big to fail, which failed again and again…

…Put simply, AJR confirms a well-known correlation: richer countries tend to be liberal democracies. But they provide zero causal evidence that it is good institutions, rather than other entangled factors, that explains divergent incomes. Edward Glaeser and his colleagues makes a similar critique, noting: “... the data [that AJR use] do not tell us whether the Europeans brought with them human capital, political institutions, or something else.”…

…That’s not to say that democracy didn’t matter in Western development — it did. But its democracy was accompanied by colonial extraction (as shown by Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa), industrial policies and trade protectionism (Ha-Joon Chang’s Kicking Away the Ladder), and cronyism among politicians and big capitalists that gradually became legalised in the form of lobbies (Richard White’s Railroaded). AJR and their followers celebrate only the first factor — and downplay or erase the rest.

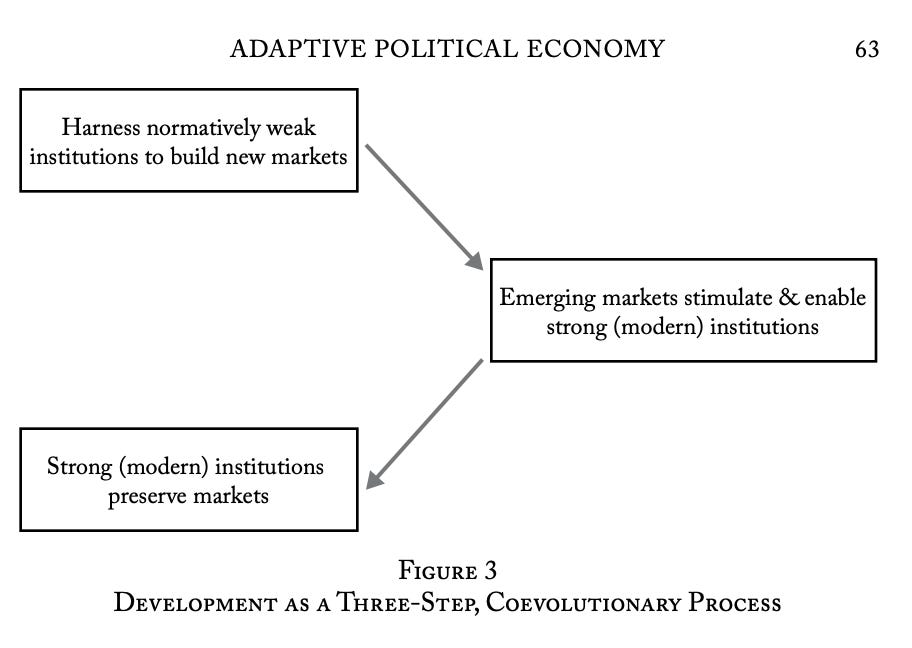

She calls the story that AJR offers a “mythologized narrative” — one that fails to offer useful prescriptions by misleading developing countries. Ang argues instead that market-building and market-preserving institutions will look different. Her work (I highly encourage everyone interested in development to read her book) uses the Chinese experience to illustrate how countries “use what they have”: they harness weak institutions to build markets, and these markets then stimulate the development of modern political institutions. And thus, as Ang summarizes: “the institutions, methods, or capacities for building new markets look and function differently from strong (modern) ones that later evolve to sustain mature markets. Indeed, market-building institutions often look wrong to first-world elites.”

Understanding the flaws in AJR’s arguments and how there are important alternative perspectives matters for our policy discourse. Already, Veerayoth Kanchoochat, who is the Deputy Leader of the People’s Party, has already written about how he “excitedly read” Robinson’s BBC Thai interview and declared that “the final curve in bringing Thailand from a middle-income to high-income country requires us to be steadfast in upholding the democratic path.”

But claims like these can be dangerous. If the promised economic windfall is not borne out after a transition to genuine democracy, such claims only set people up for future disappointment with democracy. And ironically, fans of AJR are subscribing to this view usually while fretting that Vietnam — led by a one-party communist government — is overtaking Thailand on all fronts! As Ang also wrote in her critique of AJR: “We should celebrate democracy for its intrinsic value — in giving voice to diverse, marginalized groups and holding power to account — instead of making exaggerated promises that democracy alone will make nations rich and powerful.”

Economic Upgrading Has No Easy Answers

At one point in Robinson’s BBC Thai interview, he asks: “How can we stop end the patronage system?” He then offers solutions: “making the state stronger, improving public procurement policies, ending the use of government, ending the trade of government positions for votes, reforming the election finance system, and ending vote buying.” Strangely enough, he argues: “I believe there is a solution that is not too difficult which will slowly make these mechanisms weaker.” Left unsaid is what that solution is — although implied is the building of inclusive institutions. But as we have seen, other research shows that the answer is not so simple.

Thai development currently faces several traps: a middle income trap caused by insufficient domestic innovation and an external dependency trap resulting from over-dependence on tourism and exports among others. Even if a switch existed that could toggle our institutions to become inclusive ones overnight, these traps would still require creative policy solutions that a fully democratic government could equally struggle to draw up.

The first step to escaping these traps is to accept that Thailand’s problems are structural and go beyond just a mere lack of political will. Two months ago, I wrote a response to a Thai PBS piece which made the opposition argument to AJR: that authoritarianism promotes economic growth. In that piece, I had rebutted that claim. But funnily enough, however, that Thai PBS piece does cite a piece by Richard Doner, Bryan Ritchie, and Dan Slater, which I think is worth bringing back in here:

Doner, Ritchie, and Slater argue that external threats and severe resource constraints restrict the ability of regimes to deliver “side payments” to the broad popular coalitions that sustain them. To raise revenues that can sustain high defense spending and satisfy supporters, elites in such places build effective developmental institutions that create economic growth. Without the constraints, leaders would prefer to just focus on using revenue directly for patronage. Thailand, the three argue, became an “intermediate state” because of mild systemic vulnerability.

In summary, the causes of the Thai middle income trap go far beyond just regime type — there are structural factors such as the external environment and resource constraints that require far more creative policy responses than just “build more inclusive institutions.” As T.J. Pempel (2021) describes it, the developmental success stories of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan required “fortuitous circumstances” in both the domestic and international environment — one that Thailand cannot easily just replicate even if there is political will.

The second step is to accept that a lot more nuance is required in terms of our understanding of what types of political institutions we need, beyond just exclusive vs inclusive institutions. I always recommend Richard Doner’s 2009 book The Politics of Uneven Development, which I think offers a very detailed (and helpfully Thailand-specific) view on the inhibitors of Thai economic development. As Doner writes (pages 58-63):

After a review of the statistical evidence, Przeworski and Limongi concluded that “we do not know whether democracy fosters or hinders economic growth…The more immediate influences on growth are institutions “that enable the state to do what it should but disable it from doing what it should not.” Politics clearly do matter, as we shall see, but not through regime type….

…Recent empirical work has found that a key feature of the institutional context is the degree of uncertainty perceived by economic actors. Such uncertainty is a function of institutional credibility, for example, rule predictability, security of property, fears of policy surprises, and reversals. These two conclusions – that the impact of regime type is indeterminate for growth but that institutional context does count – find confirmation in the Thai case…

…as I argue in subsequent chapters, Thai state institutions rarely exhibited consistency or inspired confidence in policy areas where (1) effective formulation and implementation required extensive information exchanges, (2) numerous actors’ participation was critical, (3) significant distributional tensions were likely to occur, and (4) opportunities for free riding were abundant. These are precisely the features of technology promotion and linkage development key to upgrading.

This argument — the need for institutional credibility — is far less sexy than simply arguing that the road out of the middle income trap is democracy and not one that is good for election banners. But that makes it no less necessary to understand. Building the sort of high-capacity institutions that Jacob Ricks and Richard Doner (2021) argue are needed to be matched with the increasingly difficult developmental tasks that Thailand faces is complex, but a necessary task.

Robinson’s BBC interview ends with him urging Thais to remember Deng Xiaoping’s pragmatism, especially his aphorism that one should “cross the river by feeling the stones” — experimenting until the best solution is found. I think we should also remember another one of Deng’s favorite slogans: to “seek truth from facts.” An accurate national conversation over Thailand’s economic underperformance means going beyond appealingly straightforward narratives and instead requires a full understanding that there are no easy solutions.

An announcement: we now have a domain name! You can now access The Coffee Parliament on coffeeparliament.com.

Admittedly, I’m translating from what I assume is the Thai translation of Robinson’s original English interview, so my apologies to James Robinson if this isn’t the word he used.

Good article covering the substance of Why Nations Fail itself, but I wish you covered what I think is the more interesting point: of course Thailand is not a failed state, but the fact that many people feel that way is telling.

People have no confidence in the government, not just in terms of their competence, but in terms of whether they hold the authority to execute actions they wish to execute.

The answer here is clearly no. The powers that the government has in reality is a fraction of their supposed authority. This isn’t a failed state per se, but it is a sham state.

Not as bad, but equally damning.

Hi Ken, sorry if this is a bit off topic but I'm just wondering, do you believe in ghosts? I recently attended an international summit in Portugal where many of the dignitaries were refreshingly open minded about the concept. Along with US Congress finally seriously investigating the decades of unavoidable evidence on UFOs, this represents a "sea change" in policy thinking. I definitely felt during my recent diplomatic involvements in Thailand that there is a lot of Dark Energy around the country. Could you perhaps do some research about whether the failure of nations can be explained by global variation in the rate of hauntings? Thanks!