A National Vote on National Security

The government pushes a referendum on border agreements with Cambodia

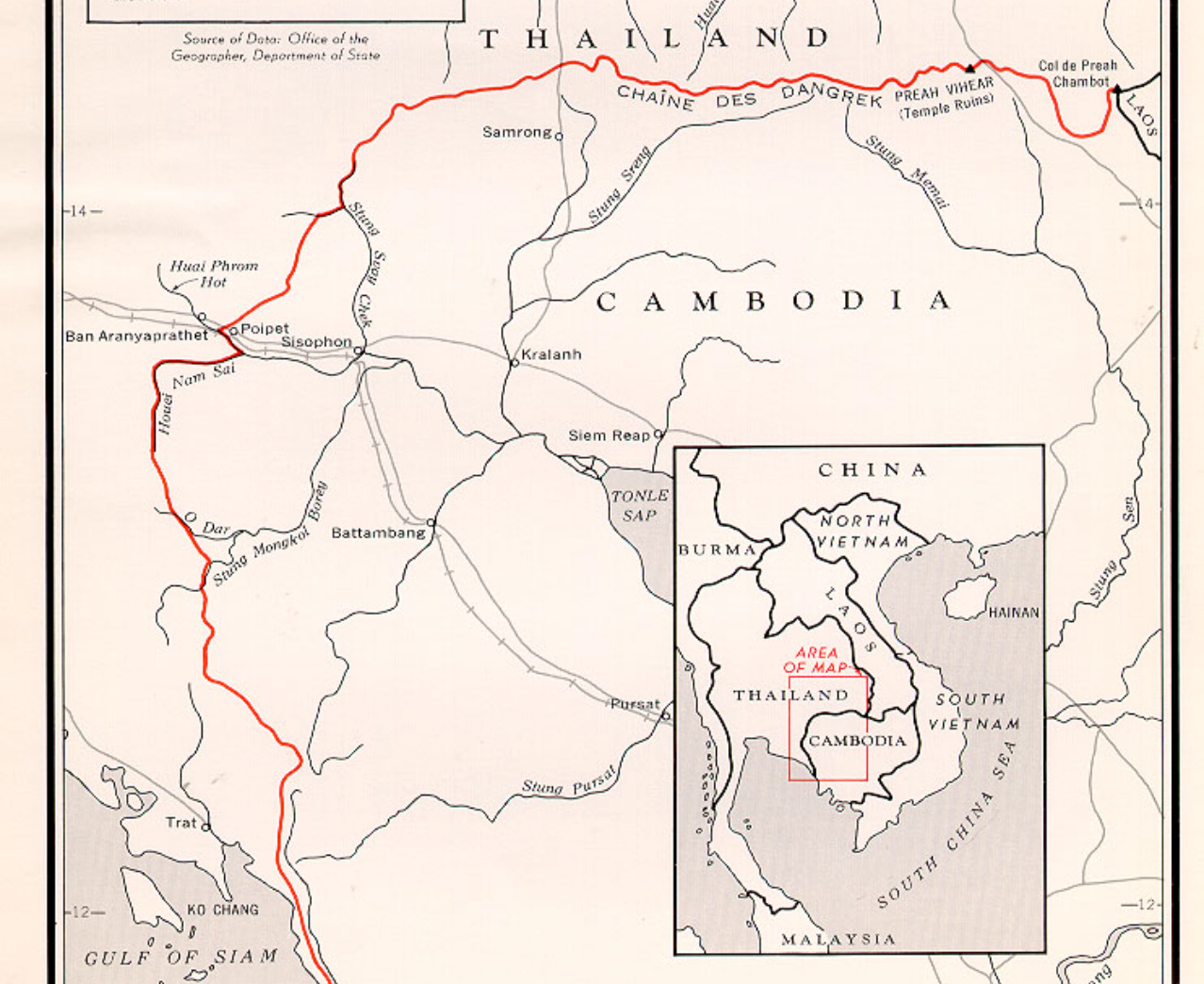

Back in late July, a military conflict erupted between Thailand and Cambodia, ending after a ceasefire was agreed to by both countries on July 28. Since then, relations between the two countries have remained tense, with the border between the two countries remaining closed.

Last week, Deputy Prime Minister Bowornsak Uwanno revealed that the government is preparing a referendum on MOU 43 and MOU 44, two agreements Thailand has with Cambodia, to be held concurrently with the general election and the constitutional reform referendum. The two agreements have become increasingly controversial after the Cambodia conflict.

First things first: what are these two agreements about? The Bangkok Post has a good explainer on what MOU 43 and 44 are. In short, MOU 43 established the Joint Boundary Commission (JBC) to survey and demarcate the Thai-Cambodian land border. MOU 44, on the other hand, created a negotiation framework for working out the maritime border between the two countries and proposed a Joint Development Area to explore petroleum and natural gas reserves before a final boundary is agreed upon.1 Crucially, neither agreement actually defines the borders. Both agreements are longstanding; MOU 43 was signed under the Chuan Leekpai government while MOU 44 was signed under the Thaksin Shinawatra government. (Worth noting that the numbers here refer to the years in which they were signed: Buddhist Era 2543 and 2544 being 2000 and 2001, respectively).

According to the Thai military, it has protested Cambodia’s violations of MOU 43 over four hundred times — which has led to renewed scrutiny over whether the agreements are benefitting the national interest. The Bhumjaithai Party calling for its repeal in late August and Pheu Thai calling for a referendum on these agreements when it was on the verge of losing power.2 But simply canceling these agreements would not be without controversy. A famous national security-focused page, ThaiArmedForce, has warned that if the two MOUs were cancelled without an alternative in place, instead of the two sides proceeding to build a new border map using modern technology, it would be likely that there would have to be a return to using the “1:200,000 map” used under previous agreements with France, which Thailand finds unfavorable.3

If, after reading all that, you think that these are highly technical issues that most people probably do not understand well, you would be correct. As The Nation puts in a recent article: a NIDA poll found that “60.76% back a referendum to cancel Thai-Cambodian MOUs 43-44, though nearly half of respondents admit poor understanding.” Almost 45 percent of respondents said that they did not understand these agreements at all, and respondents in the single digits said that they understood both well. This is hardly surprising. I imagine that most Thais had never even heard of both agreements before the conflict erupted.

It probably strikes many as a little questionable, then, to be holding a referendum on these technical agreements that less than a third of people claim to understand at any level. Indeed, there is a bit of a Brexit referendum vibe to this affair. Many voices have begun expressing skepticism about the wisdom of putting this question directly to the people. Former Bangkok Senator Rosana Tositrakul said that the two agreements “are too complex for people to throughly understand to the point where they can make a decision in a short period of time” and accused the government of lacking the courage to make a decision on their own. The conservative commentator Plew See Ngern warned that a referendum would mean people would “use emotions and feelings” to make a decision.

The Foreign Minister, Sihasak Phuangketkeow, recently said that the government is still discussing what exactly this referendum will look like. He also pledged that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs will do its best to provide necessary information to the people about MOU 43 and MOU 44. He defended the merits of holding a referendum, saying that “this is something that people are interested in and affects the national interest. We want a democratic society.” Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul stated that if a parliamentary committee finds that these agreements are not useful they should be terminated. However, he also believes that the Thai people should get to participate in this decision.

Why does the government want to push this referendum forward? After all, there is no requirement to do so: foreign agreements are not subject to popular consent. Anutin’s critics will likely take Rosana’s view and argue that they are passing the buck on to the people. Few politicians, after all, are willing now to defend these agreements. Rare exceptions include former prime minister Chuan Leekpai himself, under whom MOU 43 was concluded, who argues that it does not disadvantage Thailand. (Given that Pheu Thai has already disavowed MOU 44, and Thaksin is in prison, that agreement might truly lack committed defenders). Another theory is that a referendum on these agreements will drive up nationalist sentiment, pulling people who feel strongly about taking a tough stance on Cambodia — less likely, probably, to be opposition party voters — to the polls.

Most worryingly, a referendum on such a complex issue is the perfect example of a scenario in which voters will, as political behaviorists put it, satisfice with the use of heuristics (“shortcuts”) rather than take the time to debate the merits of the two MOUs. Instead, they will be far more likely to listen to the loudest voices — or at least the voices of the politicians they trust. Yet after whatever outcome — either a continuation or cancellation of the two agreements — few politicians will be there to accept responsibility if it turns out the national interest is not well-served. Success, after all, has many fathers, and failure is an orphan. Thailand is more likely to be best served if diplomatic and national security experts analyze the merits of the agreements and elected politicians use the power delegated by the Thai people to act on their advice.

MOU 44 became controversial last year because of speculation that the agreement could lead to Thailand losing Koh Kood, which the Ministry of Foreign Affairs denied.

This wasn’t the tone that Pheu Thai had struck previously, however.

Copying and pasting a previous footnote I used on these maps: Thailand prefers to use the 1:50,000 map, which is more detailed than the Cambodian 1:200,000 map (first developed by French surveyors). As The Nation explains, “In certain areas, Thailand’s maps may show the boundary passing through one location, while Cambodia’s maps indicate it lies hundreds of metres—or even several kilometres—away.”

I agree that putting this decision to a referendum is a cop out. I'm sure that many MPs, even government members, do not fully understand the pros and cons. But it should be an informed decision by government, not an un-informed decision based on a referendum